Russian and Chinese Infiltration Tactics Take Two Different Paths to Success

By Scott Pettigrew

Infiltration is a key strategy used for reconnaissance, targeting, raids, and ambushes, particularly by Russia and China. It enables forces to bypass strong enemy defenses when direct attacks are impractical, facilitating intelligence gathering and creating disorder behind enemy lines.

Both Russia and China use infiltration to circumvent enemy defenses when direct assaults are infeasible due to the strength of the enemy’s positions or to gain a tactical advantage. The effectiveness of infiltration tactics is evident in contemporary conflicts, such as the ongoing war in Ukraine. These tactics bypass strong defenses, support intelligence gathering and targeting, and create chaos behind enemy lines. Russian and Chinese doctrine diverge, however, regarding when and how to use infiltration tactics.

Russia has frequently used infiltration in its operations in Ukraine, including in Crimea, Donbas, and other parts of Ukraine during the early days of its so-called “special military operation.”i In 2014, the strategic use of small groups of Russian special operators and light infantry to infiltrate Ukrainian territory was particularly effective, creating chaos, seizing key terrain, and weakening the morale and effectiveness of Ukrainian border units.ii Quickly following the infiltration, the main body of pro-Russian separatist forces attacked.iii In Russian doctrine, infiltration is primarily used in conjunction with an attack. The infiltration force, acting chiefly as a reconnaissance and target acquisition element, seeks to avoid detection while moving deep behind enemy lines to identify high payoff targets such as command and control nodes and artillery firing positions.iv

Despite Ukrainian counter-infiltration measures, Russia continues to find infiltration effective at avoiding Ukrainian defenses. The initial inability of Ukrainian troops to defend against Russian infiltration tactics led the Ukrainians to adjust their doctrine, organization, and training to mitigate the threat. Beginning in 2014, the Ukrainian Army resurrected Soviet-era Spetsnaz units, specifically designed to counter Russian sabotage, reconnaissance, and infiltration teams.v In early 2023, the Russian military deployed small formations of elite soldiers to the Bakhmut area using urban infiltration tactics, a contemporary example of the tactic’s effectiveness, resulting in significant gains for the Russian forces.vi Russian forces will likely continue to employ infiltration tactics, given their effective results.

Despite lacking modern examples, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has also long employed infiltration. The PLA first started using infiltration techniques in the Chinese Civil War, which culminated in 1949, and the Korean War in the early 1950s. The Korean War tactical fight typically involved close combat and taking advantage of night operations to enable infiltration whenever possible.vii A notable example of PLA infiltration tactics occurred in November 1950 when large columns of Chinese soldiers used the cover of darkness and concealment from terrain to advance on foot along Korean ridgelines to attack Combined Forces Command elements in the flank and rear.viii The surprise assault was devastating, annihilating American forces. The US Army’s Regimental Combat Team 31 was among the units bearing the brunt of the onslaught, falling from 2,500 Soldiers to only 385 combat-ready men over five days of fighting.ix

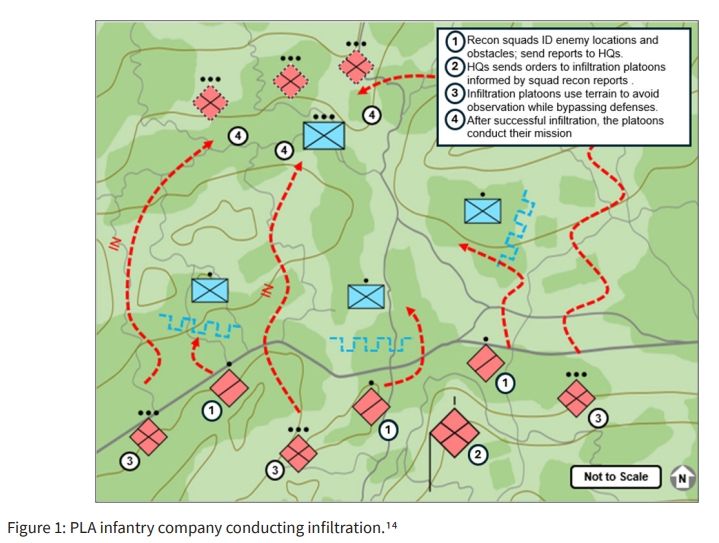

Today, PLA doctrine has evolved to emphasize infiltration tactics alongside penetrations or other assaults to isolate and eradicate enemy units. A light infantry depth attack group may infiltrate one flank of an enemy formation, while an armor-heavy depth attack group conducts an aggressive penetration of another flank. Successfully executing an infiltration attack demands significant skill and initiative from small-unit leaders. These leaders are tasked with identifying enemy weak points and then choosing their avenues of approach and methods of attack. The PLA also heavily relies on raids as part of its infiltration tactics against conventional forces.x China’s infiltration strategy differs significantly from Russia’s in that it tries to defeat the enemy with direct contact while the Russian tactic is for infiltration forces to remain undetected, performing reconnaissance and acting as spotters for artillery.

Implications for Large-scale Combat Operations

Future large-scale combat environments pose significant challenges to infiltration operations due to increased battlefield transparency and lethality.

- The proliferation of drones, signals intelligence, and space-based sensors creates a “transparent battlefield,” making undetected movement difficult. While adverse weather conditions offer some concealment, the persistent surveillance by UAS equipped with advanced optics makes detection increasingly likely. Additionally, rapid targeting enabled by networked sensors, combined with precise long-range fires and AI-assisted munitions, significantly increases the risk and likely reduce the success rate of infiltration attempts.

- To counter this, enemy forces may utilize multi-domain attacks (e.g., cyber, electronic warfare, artillery) to disrupt surveillance prior to infiltration. Additionally, the enemy will likely exploit concealed routes and employ portable counter-UAS systems for protection.

To better defend against infiltration, defending units should consider all areas they cannot observe during the day, night, and inclement weather. Once those unobserved routes are identified, defenders could adjust the security plan by repositioning troops, placing additional obstacles, employing traditional ISR assets, unattended ground sensors, trip flares, or other early warning devices to enhance observation of suspected infiltration routes. Active patrolling can also be effective at thwarting infiltration attempts.

The U.S. Army Opposing Force (OPFOR) can enhance training by incorporating Chinese PLA infiltration strategies as detailed in ATP 7-100.3 as part of the OPFOR plan. OPFOR employment of infiltration tactics would simultaneously support educating the training audience on realistic doctrinal threat tactics, while also driving stimulating training audience with the requirement to protect rear areas—a likely target in future large scale combat operations.

Notes

1 Holcomb, Franklin. 2016. “The Order of Battle of the Ukranian Armed Forces.” Institute for the Study of War. 2 Ibid. 3 Ibid. 4 Ibid. 5 Meredith, Spencer. 2024. “The Key to Ukrainian Victory Is Partnering (Not Ukrainifying) – Irregular Warfare Initiative.” Irregular Warfare Initiative. February 6, 2024. https://irregularwarfare.org/articles/the-key-to-ukrainian-victory-is-partnering-not-ukrainifying/; Dickinson, Peter. 2025. “The West Must Study the Success of Ukraine’s Special Operations Forces.” Atlantic Council. January 30, 2025. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/the-west-must-study-the-success-of-ukraines-special-operations-forces/; Momi, Rachele. 2024. “Ukrainian Special Operations Forces (UASOF).” Grey Dynamics. August 11, 2024. https://greydynamics.com/ukrainian-special-operations-forces-uasof/. 6 Bailey, Riley, Kateryna Stepanenko, Grace Mappes, Angela Howard, and Frederick W Kagan. 2023. “Russian, Offensive Campaign Assessment, February 11, 2023.” Institute for the Study of War. hxxps://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-february-11-2023. 7 Department of the Army. 2021. ATP 7-100.3, Chinese Tactics. Washington, D.C.: Headquarters, Department of the Army. 8 Appleman, Roy E. 1987. East of Chosin: Entrapment and Breakout in Korea, 1950. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. 9 Ibid.; Alexander, Bevin R. 1986. Korea: The First War We Lost. New York: Hippocrene Books. 10 Department of the Army. 2021. ATP 7-100.3, Chinese Tactics. Washington, D.C.: Headquarters, Department of the Army. 11 Ibid. 12 Ibid. 13 Ibid. 14 Ibid. 15 The Economist. 2025. “The Added Dangers of Fighting in Ukraine When Everything Is Visible.” The Economist. February 6, 2025. https://www.economist.com/europe/2025/02/06/the-added-dangers-of-fighting-in-ukraine-when-everything-is-visible.

Distribution A: Approved for public release

Categories:

Tags:

Russian and Chinese Infiltration Tactics Take Two Different Paths to Success

By Scott Pettigrew

File Size:

484KB

File Type:

Page Count:

5