China’s People’s Armed Police Presents a Significant Force Multiplier During Armed Conflict

By Captain Tyler W. Carberry, Threats Integration Officer

China’s evolving People’s Armed Police (PAP) presents a growing consideration for potential conflict.

Since 2018, China has transformed the People’s Armed Police (PAP) from a wide-ranging internal security force to a massive, well-equipped paramilitary organization that better aligns with the mission of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), suggesting the PAP must be considered when preparing for potential conflict with China. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has driven this transformation as part of its unwavering focus on maintaining Party control and China’s territorial integrity, resulting in a more militarized approach to national security, social stability, and public wellbeing.

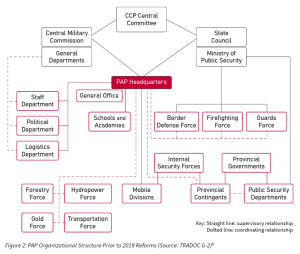

The PAP, formally established in 1982, demonstrated China’s efforts to professionalize its security apparatus to enforce laws, maintain order, and manage service activities.2 The Central Military Commission (CMC) established the PAP under dual Party and state leadership. Its roots lie in the Public Security Force, however, established in 1949. This predecessor organization underwent numerous reorganizations, with control shifting between the PLA and the Ministry of Public Security. The Public Security Force oversaw diverse functions—encompassing law enforcement, forestry, infrastructure protection, and even f irefighting—which resulted in an unfocused force with an unclear mission. This legacy continued into the PAP. To address these challenges, the CCP restructured the PAP multiple times in the past few decades.

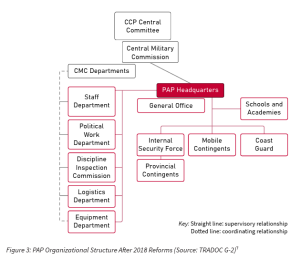

In 2018, the PAP underwent significant reforms, which subordinated the PAP directly to the Central Military Commission, replacing its previous dual civilian-military leadership (see figures 2 and 3). U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command, G-2 This restructuring placed the PAP firmly under the control of the CCP and Xi Jinping, removing local and provincial officials’ ability to independently deploy PAP units.3 This restructure also streamlined the PAP’s focus, narrowing it to three core areas: domestic stability, wartime support, and maritime rights protection. The PAP comprises approximately 1.5 million personnel.4 Its equipment includes one armored personnel carrier, various unarmored wheeled vehicles for troop transport, and both marked and unmarked patrol cars. PAP units are armed with small arms and equipped with riot control gear such as ballistic shields and K9 units. While motorized, their missions primarily involve dismounted operations, including riot control, civil disturbance response, patrolling, and safeguarding buildings or personnel.

The 2018 reforms not only consolidated military control and streamlined the PAP’s focus, they also enhanced military integration. The China Coast Guard, previously under civilian control, is now part of the PAP and thus under military command. This, in conjunction with the creation of new PAP mobile contingents—operational commands with diverse capabilities suggests greater emphasis on the PAP’s role in potential conflicts, potentially including a Taiwan contingency.6

The CMC uses the PAP to maintain stability among the civilian populace and territorial integrity within the state’s borders. The PAP is responsible for addressing internal threats to order and public or state security.8 The PAP plays a crucial role in promoting China’s national security and social stability initiatives, highlighting the country’s commitment to strengthening its internal security and active defense strategy.9 In Chinese military doctrine, the active defense strategy refers to a strategic posture that prioritizes defensive actions while allowing for the use of offensive measures as a response to external threats. This approach provides a clear signal to potential adversaries that China is prepared to defend itself and its interests, and current PAP integration with the PLA during both peacetime and war indicates that China views the PAP as an essential element of active defense to guard against encroachment, infiltration, sabotage, and harassment.

Outside of wartime, the PAP is responsible for stability operations, such as rescue and relief efforts, guarding government compounds and assets, and participating in UN peacekeeping operations globally. The PAP has also conducted civil-support operations in internal security partnerships with other singleparty socialist states. By supporting friendly regimes, China uses the PAP to mitigate perceived threats, strengthen friendly regime security, and enhance the legitimacy of its political system.

• The presence of the PAP in Hong Kong during the tumultuous 2019 protests provides a stark example of how Beijing utilizes this force for civil support operations. While the estimated 4,000 PAP personnel stationed in Hong Kong primarily remained on PLA bases, observing protest tactics alongside local police, their presence marked the largest Chinese state security deployment in the city’s history. The 2019 deployment serves as a potent reminder of the PAP’s capacity for handling civil unrest.10

• The PAP’s contributions to domestic security operations are crucial, particularly during major events. Between 2011-2012, the PAP deployed over 1.6 million personnel to secure events such as the 26th Summer Universiade, the China-Eurasia Expo, and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization Beijing Summit, implementing a range of security measures from guards and checkpoints to armed patrols.11 This domestic security role aligns with the PAP’s broader function within China’s internal security apparatus. It also demonstrates how the PAP’s involvement in securing significant events contributes to China’s national-level stability operations.

During wartime, the PAP will assume a critical combat support role for the PLA, assuming many roles that mirror the maneuver support functions of the U.S. Army. These span a broad spectrum of activities, including but not limited to protecting ground defense operations, protecting important targets and infrastructure, securing traffic and transportation lines, and defending social order in theater.12

• In ground defense operations, the PAP’s mission revolves around “two defenses and three oppositions,” actively defending national security and social stability while opposing riots, terrorism, and major criminal offenses. Its specific tasks include guarding and strengthening the protection of important targets, preventing the enemy from carrying out air attacks, preventing enemy sabotage and reconnaissance activities, and eliminating the aftereffects of air and artillery attacks.13

• Protecting high-value targets is particularly noteworthy, as the preservation of these assets can directly impact the PLA’s overall performance and success in military operations. The PAP provides armed protection over sections of key entities, such as public and nuclear facilities, logistics bases, airfields, transportation lines, water sources and conservancies, power facilities, and communication hubs. This is accomplished through concealment, deception, altering, encircling, and blocking.14

• The defense of social order in the theater of war is complex and considered a key mission for armed police units. Their specific objectives are to engage in military control of significant regions or key terrain in rear areas of conflict and handle diverse incidents that occur unexpectedly. The success of military operations is not only determined by a military’s tactical prowess but also by the nation’s ability to maintain internal order. To establish and maintain a rear area that is secure and stable, the PAP will undertake actions such as armed patrols, surveillance, intelligence gathering to monitor the society, and cooperating with local security organs to detect and prevent foreign or domestic illegal activities, riots, or disturbances.15 These actions are integral to the broader goal of ensuring social stability and mitigating the impact conflict can have on the civilian population, both in terms of enemy psychological warfare and criminal elements exploiting the situation.

In conflict, the PAP will be subordinate to the PLA Theater Joint Operations Command, and in the offense will likely be deployed in the ‘garrison zone’ while in the defense will likely be deployed to the ‘rear defensive zone.’ The latter roughly aligns with what U.S. doctrine refers to as the rear area, having the PAP strategically placed in time and space as a critical protection force, and ensuring the security of the main force’s flanks to enable the deep fight (see figures 4 and 5).

In a counter-intervention campaign against a peer adversary, the PLA will employ the PAP’s rapid reaction capabilities. As the PLA aims to incorporate the PAP into joint operations, the PAP will play a vital role in supporting flank security, safeguarding supply lines in the rear, and conducting defensive actions to repel attacks. This integration will enable the PLA to engage in combat operations more effectively.

Implications for Large-Scale Combat Operations

The PAP’s wide range of responsibilities could stretch its resources thin, potentially creating vulnerability within China’s rear area. Weaknesses in China’s rear area—such as unguarded supply lines or poorly defended logistical facilities—could be vulnerable to exploitation, potentially disrupting and degrading Chinese military operations and affecting the overall strategic balance in future conflicts. To effectively exploit these vulnerabilities, U.S. forces could engage in continuous intelligence gathering and adapt their tactics, techniques, and procedures to attack crucial capabilities with lethal and nonlethal fires.

The PAP’s role in securing rear areas, protecting critical infrastructure, and countering unconventional threats is crucial for China’s A2/AD strategy and its ability to maintain contested logistics in a largescale conflict.

• The PAP’s role in securing rear areas becomes even more crucial in a contested logistics environment. Disrupting enemy logistics is a key element of China’s strategy. The PAP’s ability to protect critical infrastructure, transportation lines, and supply depots from sabotage, special operations raids, and long-range strikes will be vital in maintaining PLA operational tempo.

• The proliferation of drones and the potential for adversaries to exploit gaps in China’s vast territory necessitates a robust counter-unconventional warfare capability. The PAP, with its distributed presence and experience in internal security, could be instrumental in detecting and neutralizing enemy infiltration, drone swarms, or sabotage attempts aimed at disrupting PLA logistics.

In dense urban environments, the PAP’s expertise in security, control, and counter-hybrid tactics will be essential to support PLA operations and counter adversary tactics that blur the lines between civilian and military spheres.

• The PLA’s focus on dense urban warfare means that the PAP’s role in maintaining order and control within cities will be crucial. This includes securing key infrastructure, managing civilian movement, and suppressing any potential unrest that could disrupt PLA operations.

• The lines between civilian and military spheres blur in urban environments. The PAP’s experience in riot control, counterterrorism, and stability operations will likely support their urban operations efforts.

In training, U.S. Army units could improve realism by including a PAP presence in the opposing forces (OPFOR) rear area. The PAP forces would support the regular military but have distinct missions. The presence would increase the OPFOR’s capacity and capabilities and allow training audiences to exploit potential vulnerabilities in PAP operations.

ENDNOTES

- Squad of the People’s Armed Police in the courtyard of the Forbidden City outside the Meridian Gate in Beijing, PRC. “People’s Armed Police squad 1.JPG.” Wikimedia Commons. October 23, 2007. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index. php?search=people%27s+armed+police&title=Special:MediaSearch&type=image

- Wuthnow, Joel. China’s Other Army: The People’s Armed Police in an Era of Reform. Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, 2019. https://inss.ndu.edu/Media/News/Article/1815868/chinas-other-army-the-peoples-armed-police-in-an-era-of-reform/.

- Zhou, Viola. “Why China’s armed Police will now only take order from Xi and his generals.” 2017. https://www.scmp.com/ news/china/policies-politics/article/2126039/reason-why-chinas-armed-police-will-now-only-take?module=perpetual_ scroll_0&pgtype=article

- Zenz, Adrian. 2018. “Corralling the People’s Armed Police: Centralizing Control to Reflect Centralized Budgets.” Jamestown. org. April 24, 2018. https://jamestown.org/program/corralling-the-peoples-armed-police-centralizing-control-to-reflectcentralized-budgets/.

- Wuthnow, Joel. China’s Other Army: The People’s Armed Police in an Era of Reform. Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, 2019. https://inss.ndu.edu/Media/News/Article/1815868/chinas-other-army-the-peoples-armed-policein-an-era-of-reform/.

- Ibid.

- Wuthnow, Joel. China’s Other Army: The People’s Armed Police in an Era of Reform. Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, 2019. https://inss.ndu.edu/Media/News/Article/1815868/chinas-other-army-the-peoples-armed-policein-an-era-of-reform/.

- Yang, Zi. 2016. “The Chinese People’s Armed Police in a Time of Armed Forces Restructuring.” Jamestown.org. March 24, 2016. https://jamestown.org/program/the-chinese-peoples-armed-police-in-a-time-of-armed-forces-restructuring.

- China Aerospace Studies Institute, ed. “In Their Own Words: Services and Arms Application in Joint Operations”. United States: China Aerospace Studies Institute, 2021.

- Torode, Greg. 2020. “Exclusive: China’s Internal Security Force on Frontlines of Hong Kong Protests.” Reuters, March 18, 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/world/exclusive-chinas-internal-security-force-on-frontlines-of-hong-kong-protestsidUSKBN2150JQ/.

- Information Office of the State Council. The People’s Republic of China. “The Diversified Employment of China’s Armed Forces.” English.www.gov.cn. 2013. https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2014/08/23/content_281474982986506. htm.

- China Aerospace Studies Institute, ed. “In Their Own Words: Services and Arms Application in Joint Operations”. United States: China Aerospace Studies Institute, 2021.; Wuthnow, Joel. China’s Other Army: The People’s Armed Police in an Era of Reform. Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, 2019. https://inss.ndu.edu/Media/News/Article/1815868/ chinas-other-army-the-peoples-armed-police-in-an-era-of-reform/.

- China Aerospace Studies Institute, ed. “In Their Own Words: Services and Arms Application in Joint Operations”. United States: China Aerospace Studies Institute, 2021.

- Yi, Xu. 2021. “Law of the People’s Republic of China on the People’s Armed Police – Ministry of National Defense.” Mod.gov. cn. 2021. http://eng.mod.gov.cn/xb/Publications/LR/4888359.html. 15 China Aerospace Studies Institute, ed. “In Their Own Words: Services and Arms Application in Joint Operations”. United States: China Aerospace Studies Institute, 2021.

- Squad of the People’s Armed Police in the courtyard of the Forbidden City outside the Meridian Gate in Beijing, PRC. “People’s Armed Police squad 1.JPG.” Wikimedia Commons. October 23, 2007. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index. php?search=people%27s+armed+police&title=Special:MediaSearch&type=image

Distribution A: Approved for public release

Categories:

Tags:

China’s People’s Armed Police Presents a Significant Force Multiplier During Armed Conflict

By Captain Tyler W. Carberry, Threats Integration Officer

File Size:

778 KB

File Type:

Page Count:

7